The beauty of mechanical watches is that they pay tribute to the past while representing the future. IWC, like all watch companies founded in the 19th century, produced pocket watches for decades.

While pocket watches appear today as anachronisms, the principles underlying IWC’s great pocket watch tradition continue and, indeed, prevail. The essential time-keeping mechanism, the Swiss lever escapement, works basically the same in today’s wristwatches as in history’s pocket watches. Mechanical watches, old and new, tell time in the same way. Most importantly, for IWC the highest principles of fine engineering and meticulous craftsmanship continue to evolve and distinguish the brand.

IWC’s long and proud pocket watch tradition began with its American founder, F.A. Jones, who established the company in 1868. His now-called Jones movements began in 1869 until he left the company in 1875, although some models were assembled and sold after his departure, still bearing Jones’ highly regarded emphasis on fine craftsmanship.

The pocket watches with Jones’ movements exemplified fine watchmaking of their era and cutting-edge techniques. Newly patented technologies were employed, as well as other innovative characteristics, such using a longer index or “Jones needle” to assist with fine regulation of the movement. The Jones movements generally were finely finished, so much so that some even were cased with display backs. These Schaffhausen-made pocket watches were primarily sold in the United States, which in the second half of the 19th century was a center of modern watchmaking. U.S. companies then produced large quantities of watches with reliable quality, and as such were dominating the world market.

Around 26,000 Jones movements were produced, although by 1874 only 6,000 were sold. Six basic patterns were made: patterns B, D, E, H, R and S, and several variations existed within each pattern. Three patterns were made in both key-wound and stem-wound variations, but most of the Jones watches were stem-wound and stem-set, a high-end characteristic for this era.

IWC’S LONG AND PROUD POCKET WATCH TRADITION BEGAN WITH ITS AMERICAN FOUNDER, F.A. JONES, WHO ESTABLISHED THE COMPANY IN 1868.

After Jones left IWC, in 1876 another American, Frederick Seeland, became CEO and on the one hand produced a less expensive movement with full plates, which mostly was sold in the British empire. These watches, known today as Seelands, used movements designated as Calibers 18 through 26. (It should be noted that the nomenclature for those movements, and other IWC movements discussed below, was based on a consecutive calibre list prepared in 1921. Since collectors today are familiar with the caliber numbers from that list, the following text names pre-1921 movements based on that 1921 list).

Those movements mostly had full plates, fewer jewels and lesser finishing. The movements, too, were less state-of-the-art, with most being key-wound and key-set. To collectors, these models appeal more for their rarity, with around 20,000 total Seeland movements having been made, and for their historical significance.

On the other hand, Seeland also launched a new generation of three-quarter plate movements in 1878 which later became known as the famous “à bascule piliers”. Documents at IWC corporate archives show that most probably calibers 18, 20, 21, 22, 23 were designed before 1880.

Seeland’s strategy for IWC failed in 1879 and IWC then was acquired by the Rauschenbach family from Schaffhausen. For approximately the next 10 years, IWC’s products went through a transitional period. Some of the pocket watches, like the Calibre 28 “à bascule piliers”, were similar to traditional prior models, such the IWC three-quarters plate Calibre 22 Seeland. Some were more avant-garde, like the digital display pocket watches that used a system licensed from an Austrian engineer, Josef Pallweber.

The basic movements of the so-called IWC Pallweber pocket watch movements were actually part of the “Elgin“ family of IWC movements, although today no one knows with certainty why they were so-named. In the mid-1880s, IWC produced several movements, many closely similar to each other, with the Elgin name. Many of the Elgin movements are of interest primarily to pocket watch collectors, again for their rarity more than their finesse. Many of the watches with calibre numbers in the 30s and 40s were produced in extraordinarily small quantities. These movements can be considered as transitional movements, which bridged a gap from the early Jones and Seeland production to more “modern” pocket watch movements.

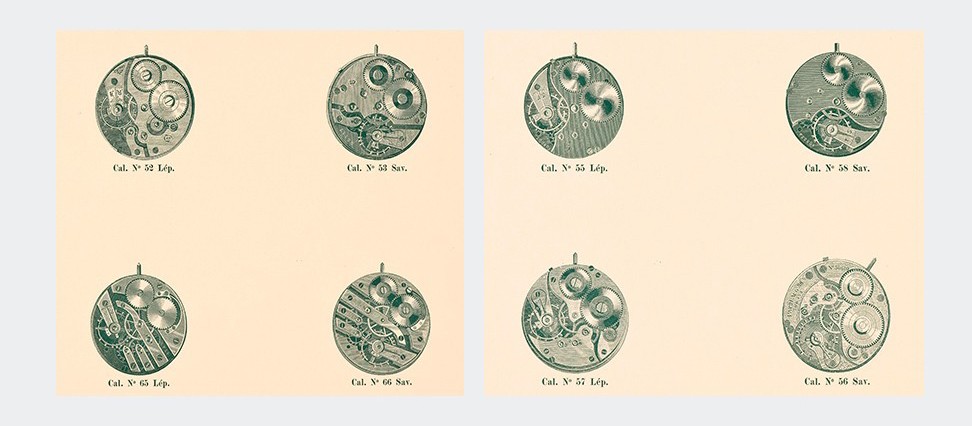

But the Elgin III movements, as launched in 1886, also served as the forerunner of the “IWC Calibre” movement that was introduced in 1888. The IWC Calibre movement subsequently became known as Calibre 52 and, in a companion “hunter” or Savonette version (with the winding stem at 3 o’clock), Calibre 53. Over 460,000 Calibre 52 and 53 movements were produced from 1888 to 1940. This was the IWC movement produced over the longest timespan, and the most common type of movement found today in antique IWC pocket watches.

These movements were produced with many modifications over the years, from changes in the regulator system to differences in height. There even was a change from subsidiary seconds to indirect central seconds. In 1940, the last 1,200 of this movement, Calibre 52 T.S.C., were produced with central seconds for IWC’s famous Big Pilot’s Watch of 1940 and a British Navy deck watch.

All these “Calibre IWC” movements, Calibres 52s and 53s, and their watches can be considered as “tractors”: strong and durable movements with excellent accuracy. But from a cosmetic perspective they lacked a certain finesse valued today by many collectors. Generally, the plates and bridges were undecorated brass and the movements were relatively thick. However, they represented the IWC philosophy of the era, with strong and practical craftsmanship from Schaffhausen.

IWC also produced, towards the end of the 19th century and in the first decades of the 20th century, pocket watches with other movements. In 1889 the company also produced a “Schaffhausen Calibre” 55 (Lépine) and 58 (Hunter), followed shortly thereafter by the “split-plate movements “Elgin Américain”, Calibre 57 in a Lépine version and Calibre 56 in a companion Savonette version. (Calibre 57 a few years later was renamed Calibre 58.) Calibres 56/57 were also produced in quantity, with just under 140,000 manufactured over a 42 year span.

MANY OF THE ELGIN MOVEMENTS ARE OF INTEREST PRIMARILY TO POCKET WATCH COLLECTORS, AGAIN FOR THEIR RARITY MORE THAN THEIR FINESSE.

IWC also made its first “finger bridge” movement, Calibre 65, starting in 1893. Rather than the heavier and thicker three-quarters plate movement of that era, these movements instead had narrow bridges and cocks supporting each wheel, which allowed for a somewhat thinner and more elegant movement. In addition to a companion Calibre 66, some slight modifications lead later to the Calibres 73 and 74 finger bridge movements. These were produced from 1913 to 1931 in 67,500 examples. Additionally, a very rare and beautiful IWC finger bridge movement was Caliber 69. At 4.7 mm in height and 16 lignes in diameter, this finger bridge Lépine movement was launched in 1898. Only about 2,100 were produced.

Starting in 1904, IWC also produced a pocket watch with a particularly unusual movement — Calibre 71 and, for hunter or Savonette models, Calibre 72. Unlike IWC’s typical movements with three-quarter plates or finger-bridges, these movements had curved bridges and cocks that were almost lyrical in design. These movements are called “fishtail” because of their curves. Many collectors consider them among the most beautiful movements ever produced, but only 600 of each movement were made from 1904 until 1917. They all are highly collectible, especially the Calibre 71 IWC pocket watches produced in 1917 in only 180 examples for the British Royal Navy.

In most instances, the dials of all these early pocket watches were well-done but unremarkable. Enamel was used on a brass base, with classic number configurations. Until around 1900 most IWC pocket watch dials had Roman numerals and thereafter Arabic numerals were often used.

The early IWC pocket watch cases often were elaborately engraved or decorated. Some, especially the Jones models from the 1870s and other models in the 1890s, had elaborate scenes or intricate engravings. By the time of the 1920s and the Art Deco era, thin cases, usually housing the slim Calibres 73 or 74 movements, often had Egyptian enamel motifs in fine engravings. In the 1920s the enamel dials also became more stylized, often with fanciful Arabic numerals and more “modern” hands.

From 1917 to 1921 IWC produced 10,500 examples of one new pocket watch movement that in many ways differed from the classic thick Swiss pocket watch movements, as exemplified by Calibre 52, or even its traditional but thinner finger bridge movements. Those new movements were Calibre 77s, and most were sold to the North American market. Perhaps intending to meet the perceived demands of those markets, these movements were special.

Calibre 77 might be considered the first of IWC’s more contemporary pocket watch movements. It moved away from the unadorned brass bridges to shinier nickel-plated ones, decorated with Geneva stripes. Many of the movements now had 21 jewels, unlike the more typical 16 or 17 jeweled other IWC pocket watch movements. Some Calibre 77s even were rumored to have 25 jewels, although no example has been found today.

After that limited launch, IWC produced its first pocket watch movements in the late 1920s that indirectly survive even today. The ultra-thin Calibre 95 was first made in 1927 and, with a variation having shock resistance, was continued until 1973. A similar but slightly thicker pocket watch movement, the Calibre 97 was launched in 1930 and a companion hunter model was produced starting in 1936. If one finds today an IWC pocket watch from the 1950s or 60s it almost certainly will have one of these movements, all nicely finished with nickel-plating and stripes.

Although these movements were fine examples of horology, with changing tastes in the 1930s and thereafter, not many were made. From 1927 to 1973, IWC’s total production of pocket watch movements was less than 40,000.

As pocket watches became increasingly less popular and wristwatches grew in popularity, by the mid-1930s IWC primarily produced wristwatches.

However, IWC kept its pocket watch tradition alive in several ways, not the least of which was still continuing to produce pocket watches but in relatively small quantities. When the ‟quartz crisis” hit the entire Swiss watch industry in the 1970s, for a time IWC even considered becoming a specialist pocket watch producer. Starting 1977 with the famous Reference 5500 many new pocket watch models were introduced by IWC, although sales and therefore production was limited.

Pocket watch movements also were used in IWC wristwatches. In addition to the Big Pilot watches of 1940, in 1939 first IWC produced a series of wristwatches, known as Reference 325, with IWC Calibre 74 for two Portuguese watch dealers. This became the birth of IWC’s famous Portuguese model wrist watches. Starting in 1944, IWC also used its Calibre 98 movement in Reference 325 Portuguese wristwatches. In very limited quantities those Portuguese wristwatches were made until 1981.

IWC then revived its famous and rare Portuguese models when celebrating its 125th anniversary in 1993. The Reference 5441 Jubilee Portuguese was chosen in 1993 as a limited edition because it fully represented IWC’s tradition, and contained an in-house Calibre 98 based pocket watch movement (called Calibre 9828, with the additional numbers indicating the addition of shock resistance and also special anniversary engraving).

In 2006, IWC revived production of its famous Calibre 98 pocket watch movement, this time as Calibre 98290 and initially used in limited edition “Jones” wristwatch models, which celebrated IWC’s founder and the original Jones pocket watch movements. The Calibre 98 base of these watches was modified to look like a Jones pocket watch movement, with a three-quarters plate added as well as the distinctive Jones regulating index. These movements, with modifications and technical improvements, were then used in many otherIWC wristwatches that had manual winding movements, including other Portuguese models.

Even when pocket watch movements were not used in IWC’s contemporary wristwatches, their movements often paid homage to IWC’s great pocket watch tradition. The first example of this is IWC’s famous Calibre 5000 introduced in 2000. That movement marked the revival of IWC’s in-house movement production, and the designers clearly indicated that it was based in many respects on IWC’s renowned pocket watch calibres, but this time as an automatic pocket watch movement for a wristwatch.

WHEN THE ‟QUARTZ CRISIS” HIT THE ENTIRE SWISS WATCH INDUSTRY IN THE 1970S, FOR A TIME IWC EVEN CONSIDERED BECOMING A SPECIALIST POCKET WATCH PRODUCER.

The IWC Calibre 5000 movement evolved over the past 15 years in many variations, and has been used in numerous models in this and the past decade, including Reference 5001, the Portuguese Automatic, and all the Big Pilot Watch models, starting with Reference 5002 and continuing to References 5004 and now Reference 5009. In all instances, these models were not large merely as a concession to popular trends but also because their movements are based on, and pay homage to, IWC’s great pocket watch movements.

In a sense, IWC’s pocket watches are alive today, because their movements serve as the foundation for many IWC modern wristwatch movements. History repeats itself, always. This is particularly good news given IWC’s grand pocket watch heritage. It is the tradition of “Probus Scafusia”: good, solid craftsmanship from Schaffhausen. In fact, it’s more than good. It’s superior.